The phrase postfeminism for me calls to mind the late 2010's more so than the early 00's. Obviously this is in no small part because I was two years old when Sex and the City premiered; but more to the point, this era in American political culture emblematized the problems with then-dominant vernacular feminism in such a highly visible way that the postfeminist cultural formations that followed (and which still loom quite large) seem nearly inevitable. Writing a decade prior, Sarah Banet-Weiser raises two of the essential issues that, evidently, we failed to redress in the interim:

"Are we simply living in, as Naomi Klein claims, a 'Representation Nation,' where visibility in the media takes precedence over 'real' politics? Again, for those who consider themselves to be third-wave feminists, such as Jennifer Baumgardner and Amy Richards, the argument is made that this kind of media visibility is absolutely crucial to politics." (208)

"As a contemporary social and political movement, then, feminism itself has been rescripted (though not necessarily disavowed) so as to allow its smooth incorporation into the world of commerce and corporate culture- what Robert Goldman calls 'commodity feminism.'" (209)

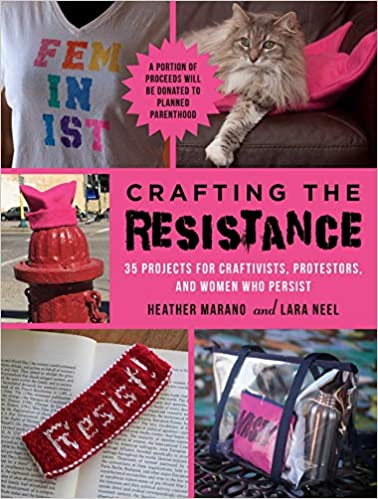

Pivotally here, Banet-Weiser positions this rescripting into terms amenable to media commodification not as a byproduct of postfeminism but of dominant contemporary feminism itself. We might wager that this watering down emerges as a response to the currents of postfeminism that MacRobbie rightly sees floating in the ether of Y2K pop culture; nonetheless, it's meaningful that the dominant form of feminism itself, rather than the response to it, is here presented as having so thoroughly rid itself of radical potential. This is the dominant vernacular feminism going into the 2016 presidential election, an era that wove this denuded feminism more thoroughly into mainstream discourse both as a real reminder of the necessity of resistant political formations and as a farcical demonstration of how unprepared for resistance this commodified mass feminism was. At the same time that the word "resist" was shoved down our collective throat, the capacity for resistance was proved to be minimal, as positions or actions taken under the banner of feminism were generously expanded to include and largely coalesce around voting for Hillary Clinton (and readily leveling accusations of misogyny against those critical of her politics or of the DNC actively manufacturing her primary victory), wearing a so-called pussyhat, and so many other emblems of 2017's liberal cringe (see below, and note the site on which it's for sale https://www.amazon.com/Crafting-Resistance-Projects-Craftivists-Protestors/dp/1510731385 ).

This is the cultural landscape against which two of my arch nemeses came to dominate a niche in the podcasting world: Anna Khachiyan and Dasha Nekrasova of the somehow popular podcast Red Scare. Red Scare meets each of Jess Butler's criteria for postfeminism to a tee; it

"1. implies that gender equality has been achieved and feminist activism is thus no longer necessary;

2. defines femininity as a bodily property and revives notions of natural sexual difference;

3. marks a shift from sexual objectification to sexual subjectification;

4. encourages self-surveillance, self-discipline, and a makeover paradigm;

5. emphasizes individualism, choice, and empowerment as the primary routes to women’s independence and freedom; and

6. promotes consumerism and the commodification of difference." (44)

While maintaining an increasingly oblique relationship to leftism that allowed, for a time, their transparently conservative social values to receive the benefit of the doubt, Red Scare can't quite be called a political podcast. They do engage in cultural critique, which I'll readily confess to having enjoyed for a period around 2019, when their willingness to name the embarrassments of mass liberal #resistance culture what they were was seemingly rare and quite refreshing. Unlike the cultural products MacRobbie and others discuss, I think Red Scare might actually embrace the term postfeminist, and at the time I started listening to them, the dawn of their cultural ascendancy, a good swathe of the public likely felt ready to embrace it as well. The term feminism had been so thoroughly vacated of meaning by the #resist era that I was on some level probably soothed by hearing two women with vague claims to the left readily put it to bed. As my prose is suggesting, I don't hold this to be a tenable position, but I also see the reactionary postfeminism of the late 2010's and early 2020's as an all too predictable response to the cooptation of liberal feminism, and the capitalism and transphobia in which dominant representational feminisms traffic leave little enthusiasm for a left to want to reclaim its banner. Throw a stone in Echo Park and you're bound to hit a well-to-do and worryingly skinny young white woman who would self-describe as "trad-cath" (espousing traditional values including some nebulous relationship to Catholicism), a mini Anna Khachiyan who's renounced claims to political identity in favor of perfecting aesthetics.

As MacRobbie and Banet-Weiser both point out, a well-honed sense of ironic detachment is the pivotal ingredient in postfeminism. While this detachment shoots resistance in the foot, it's also the invited affect of our era, a cultivated defense toward a hostile world's worsening economic realities and the faux-conciliatory cultural formations it increasingly throws our way. Untethering the signifier feminism from political and cultural formations responsible for the increasing worsening of our world might help claw the left out of this pit; with the increasing likelihood of the pussyhat brigade coming out in full force for a Harris 2024 ticket, I won't be holding my breath.

No comments:

Post a Comment